复杂性通过以下三种段落中描述的三种一般方式体现出来。这些表现形式中的每一个都使执行开发任务变得更加困难。

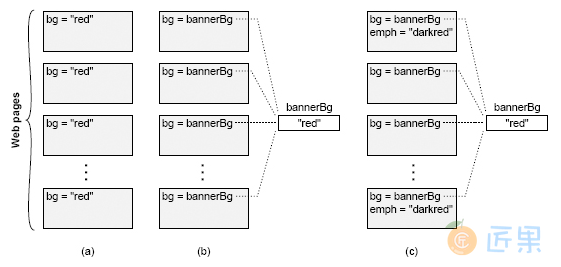

变更放大:复杂性的第一个征兆是,看似简单的变更需要在许多不同地方进行代码修改。例如,考虑一个包含几个页面的网站,每个页面显示带有背景色的横幅。在许多早期的网站中,颜色是在每个页面上明确指定的,如图 2.1(a)所示。为了更改此类网站的背景,开发人员可能必须手动修改每个现有页面;对于拥有数千个页面的大型网站而言,这几乎是不可能的。幸运的是,现代网站使用的方法类似于图 2.1(b),其中横幅颜色一次在中心位置指定,并且所有各个页面均引用该共享值。使用这种方法,可以通过一次修改来更改整个网站的标题颜色。

认知负荷:复杂性的第二个症状是认知负荷,这是指开发人员需要多少知识才能完成一项任务。较高的认知负担意味着开发人员必须花更多的时间来学习所需的信息,并且由于错过了重要的东西而导致错误的风险也更大。例如,假设 C 中的一个函数分配了内存,返回了指向该内存的指针,并假定调用者将释放该内存。这增加了使用该功能的开发人员的认知负担。如果开发人员无法释放内存,则会发生内存泄漏。如果可以对系统进行重组,以使调用者不必担心释放内存(分配内存的同一模块也负责释放内存),它将减少认知负担。

系统设计人员有时会假设可以通过代码行来衡量复杂性。他们认为,如果一个实现比另一个实现短,那么它必须更简单;如果只需要几行代码就可以进行更改,那么更改必须很容易。但是,这种观点忽略了与认知负荷相关的成本。我已经看到了仅允许使用几行代码编写应用程序的框架,但是要弄清楚这些行是什么极其困难。有时,需要更多代码行的方法实际上更简单,因为它减少了认知负担。

图 2.1:网站中的每个页面都显示一个彩色横幅。在(a)中,横幅的背景色在每页中都明确指定。在(b)中,共享变量保留背景色,并且每个页面都引用该变量。在(c)中,某些页面会显示其他用于强调的颜色,即横幅背景颜色的暗色;如果背景颜色改变,则强调颜色也必须改变。

未知的未知:复杂性的第三个症状是,必须修改哪些代码才能完成任务,或者开发人员必须获得哪些信息才能成功地执行任务,这些都是不明显的。图 2.1(c)说明了这个问题。网站使用一个中心变量来确定横幅的背景颜色,所以它看起来很容易改变。但是,一些 Web 页面使用较暗的背景色来强调,并且在各个页面中明确指定了较暗的颜色。如果背景颜色改变,那么强调的颜色必须改变以匹配。不幸的是,开发人员不太可能意识到这一点,所以他们可能会更改中央 bannerBg 变量而不更新强调颜色。即使开发人员意识到这个问题,也不清楚哪些页面使用了强调色,因此开发人员可能必须搜索 Web 站点中的每个页面。

在复杂性的三种表现形式中,未知的未知是最糟糕的。一个未知的未知意味着你需要知道一些事情,但是你没有办法找到它是什么,甚至是否有一个问题。你不会发现它,直到错误出现后,你做了一个改变。更改放大是令人恼火的,但是只要清楚哪些代码需要修改,一旦更改完成,系统就会工作。同样,高的认知负荷会增加改变的成本,但如果明确要阅读哪些信息,改变仍然可能是正确的。对于未知的未知,不清楚该做什么,或者提出的解决方案是否有效。唯一确定的方法是读取系统中的每一行代码,这对于任何大小的系统都是不可能的。甚至这可能还不够,因为更改可能依赖于一个从未记录的细微设计决策。

良好设计的最重要目标之一就是使系统显而易见。这与高认知负荷和未知未知数相反。在一个显而易见的系统中,开发人员可以快速了解现有代码的工作方式以及进行更改所需的内容。一个显而易见的系统是,开发人员可以在不费力地思考的情况下快速猜测要做什么,同时又可以确信该猜测是正确的。 第十八章:代码是显而易见的 讨论使代码更明显的技术。

Complexity manifests itself in three general ways, which are described in the paragraphs below. Each of these manifestations makes it harder to carry out development tasks.

Change amplification: The first symptom of complexity is that a seemingly simple change requires code modifications in many different places. For example, consider a Web site containing several pages, each of which displays a banner with a background color. In many early Web sites, the color was specified explicitly on each page, as shown in Figure 2.1(a). In order to change the background for such a Web site, a developer might have to modify every existing page by hand; this would be nearly impossible for a large site with thousands of pages. Fortunately, modern Web sites use an approach like that in Figure 2.1(b), where the banner color is specified once in a central place, and all of the individual pages reference that shared value. With this approach, the banner color of the entire Web site can be changed with a single modification. One of the goals of good design is to reduce the amount of code that is affected by each design decision, so design changes don’t require very many code modifications.

Cognitive load: The second symptom of complexity is cognitive load, which refers to how much a developer needs to know in order to complete a task. A higher cognitive load means that developers have to spend more time learning the required information, and there is a greater risk of bugs because they have missed something important. For example, suppose a function in C allocates memory, returns a pointer to that memory, and assumes that the caller will free the memory. This adds to the cognitive load of developers using the function; if a developer fails to free the memory, there will be a memory leak. If the system can be restructured so that the caller doesn’t need to worry about freeing the memory (the same module that allocates the memory also takes responsibility for freeing it), it will reduce the cognitive load. Cognitive load arises in many ways, such as APIs with many methods, global variables, inconsistencies, and dependencies between modules.

System designers sometimes assume that complexity can be measured by lines of code. They assume that if one implementation is shorter than another, then it must be simpler; if it only takes a few lines of code to make a change, then the change must be easy. However, this view ignores the costs associated with cognitive load. I have seen frameworks that allowed applications to be written with only a few lines of code, but it was extremely difficult to figure out what those lines were. Sometimes an approach that requires more lines of code is actually simpler, because it reduces cognitive load.

Figure 2.1: Each page in a Web site displays a colored banner. In (a) the background color for the banner is specified explicitly in each page. In (b) a shared variable holds the background color and each page references that variable. In (c) some pages display an additional color for emphasis, which is a darker shade of the banner background color; if the background color changes, the emphasis color must also change.

Unknown unknowns: The third symptom of complexity is that it is not obvious which pieces of code must be modified to complete a task, or what information a developer must have to carry out the task successfully. Figure 2.1(c) illustrates this problem. The Web site uses a central variable to determine the banner background color, so it appears to be easy to change. However, a few Web pages use a darker shade of the background color for emphasis, and that darker color is specified explicitly in the individual pages. If the background color changes, then the the emphasis color must change to match. Unfortunately, developers are unlikely to realize this, so they may change the central bannerBg variable without updating the emphasis color. Even if a developer is aware of the problem, it won’t be obvious which pages use the emphasis color, so the developer may have to search every page in the Web site.

Of the three manifestations of complexity, unknown unknowns are the worst. An unknown unknown means that there is something you need to know, but there is no way for you to find out what it is, or even whether there is an issue. You won’t find out about it until bugs appear after you make a change. Change amplification is annoying, but as long as it is clear which code needs to be modified, the system will work once the change has been completed. Similarly, a high cognitive load will increase the cost of a change, but if it is clear which information to read, the change is still likely to be correct. With unknown unknowns, it is unclear what to do or whether a proposed solution will even work. The only way to be certain is to read every line of code in the system, which is impossible for systems of any size. Even this may not be sufficient, because a change may depend on a subtle design decision that was never documented.

One of the most important goals of good design is for a system to be obvious. This is the opposite of high cognitive load and unknown unknowns. In an obvious system, a developer can quickly understand how the existing code works and what is required to make a change. An obvious system is one where a developer can make a quick guess about what to do, without thinking very hard, and yet be confident that the guess is correct. Chapter 18 discusses techniques for making code more obvious.